infossil – AD VITAM | 2002

(English translation below) (Also available on medium)

INFOSSIL – AD VITAM

Ein Gespräch zwischen Peter Weibel und Michael Saup, Karlsruhe, 2002

Saup: Wo ich aufgewachsen bin, konnte ich mit niemandem sprechen. Ich bin daher ins Virtuelle gegangen, in die Zukunft oder die Vergangenheit. Die Navigation im Nichts war die zentrale Grundlage des Überlebens.

Weibel: Auch ich habe mir als Kind eigene Welten geschaffen. Vielleicht ist die Voraussetzung, um Künstler zu werden, dass man automatisch beginnt, sich andere Welten zu suchen. Es gab niemanden, mit dem ich reden wollte. Im Gegenteil, ich habe versucht, mich von der ganzen sozialen Gemeinschaft zurückzuziehen. Die normale Außenwelt war für mich eher störend. Du hast dich auch früh abgesondert?

Saup: ja.

Weibel: … und mit dir selbst dich unterhalten bis zurück über Jahrhunderte.

Saup: Das erste Medium, das ich bewusst benutzt habe, waren Träume. Danach war es die Musik, dann die Kamera meines Vaters, die in einem Schrank lag. Ich habe sie nachts geklaut, um dann in meinem Zimmer kurze Szenen zu belichten. Um 1980 habe ich angefangen, mit Computern zu arbeiten. Ich habe gesehen, dass ich hacken kann, dass ich dafür jedoch gar nicht programmieren können muss. Ich kann einfach in die Codierung eingreifen, die da ist. Ich kann sie zerstören und es passiert etwas Neues. Das hat mich fasziniert. All das war eine Hilfe, dem Jetzt zu entkommen oder eine Straße in die Zukunft zu bauen.

Weibel: Dass du mit Träumen begonnen hast, passt zu meiner Theorie, dass Medien und Technik einer Morphologie des Begehrens entspringen. Die Wünsche, das Begehren, die Sehnsüchte suchen sich irgendeine Äußerungsform, eine Gestalt, in der sie sich artikulieren. Vielleicht setzen die Medien also nur die Arbeit der Träume fort. Man kommuniziert mit Dingen, die weder räumlich noch zeitlich da sind. Durch die Medien kann ich die Distanz, die Dislokation, überbrücken. Träume machen genau das: sie machen das Abwesende anwesend. Man träumt und schafft sich dadurch neue Erfahrungen.

escape from the program [of experience]

Weibel: Aber die Erfahrung bildet auch ein Gefängnis. Wenn ich beispielsweise fünfmal einem Menschen Brot anbiete und er mich jedes Mal dafür schlägt, dann weiß ich einfach, dass Brot zu geben bedeutet, geschlagen zu werden. Diese Erfahrung wird man nicht mehr los. Eine Katze, die auf eine heiße Herdplatte gesprungen ist, wird es nicht wieder tun.

Es wäre eigentlich besser, man könnte diese Erfahrung löschen, auch auf die Gefahr hin, dass man sich wieder verbrennt. Aber dann kann man immer wieder aufs neue der Welt begegnen: mit dieser Unbefangenheit, mit diesem Optimismus. So jedoch werden die Menschen skeptisch und misstrauisch. Sie sind in ihre Erfahrung eingeschlossen. Ich versuche immer wieder, diese Erfahrung zu löschen. Der Preis ist sehr hoch, aber ich möchte mich nicht in diese Erfahrung, in dieses Gefängnis einschließen lassen.

Saup: interessante Idee …

Weibel: Du erschaffst dir eine Geschichte. Dann wirst du Gefangener dieser Geschichte, Erfahrung zielt darauf aus, Schmerz und Schaden zu vermeiden. Gleichzeitig wird dadurch meine Fähigkeit, neue Erfahrungen zu machen, eingeschränkt. Mein Horizont wird immer enger, und je älter man wird, umso schlimmer wird dies.

Gott sei Dank haben Jugendliche kaum Erfahrungen. Aufgrund mangelnder Erfahrung stürzen sie sich in Abenteuer, von denen ihnen die Erfahreneren abraten. Doch da sie nicht Gefangene sind der Geschichte, machen sie es und es geht gut.

Saup: Das Gefängnis der Erfahrung ist besonders tragisch, da lokale Erfahrungen natürlich auf das Globale angewendet werden. Die Erfahrung bewahrt dich davor, überhaupt etwas kennenzulernen, was sich außerhalb deines lokalen Kulturkreises befindet.

Weibel: Du wirst ein Gefangener, a “prisoner of the particular”, ein Gefangener des Besonderen. An einem anderen Ort, in anderen Kulturkreisen könnte das Individuum ganz anders agieren. Aber die Erfahrung der Vielheit ist versperrt. An die Erfahrung des Universellen glaube ich nicht. Es gibt wenig Konstanten. Es gibt eben nur die Vielheit der Unterschiede. Aber diese Vielheit wird einem nicht zugänglich gemacht, da man sich zu sehr an die lokale partikuläre Erfahrung bindet, die man hier und jetzt gemacht hat.

Die Kunst sollte es ermöglichen, Erfahrungen zu löschen, indem sie neue Erfahrungen machen lässt. Das gelingt aber nur selten.

escape from the program [of nature]

Weibel: Es gibt Wissen, das die Evolution eingeprägt hat. Das Erdhörnchen weiß, wie es auf eine Klapperschlange zu reagieren hat, ohne je eine Klapperschlange gesehen zu haben. Das ist dieser Chip. Die Reaktion des Tieres ist nicht erlernt, die historische Erfahrung ist vielmehr genetisch eingeprägt. Nur so kann die Natur ihre Geschöpfe überleben lassen. Die Tiere sind Gefangene der geschichtlichen Erfahrung.

Saup: Das Programm ist …

Weibel: Wir sind Gefangene des Programms, wollen aber mehr sein. Wenn wir Menschen sein wollen, müssen wir den Preis bezahlen, Erfahrungen auch wieder zu löschen. Dann müssen wir das Programm löschen. Aber das tun nur die wenigsten, da es Risiken birgt und weil es zu Schaden führen kann. Es würde sich eigentlich auszahlen. Um sich als Mensch weiterzuentwickeln, wäre es notwendig, eben diese Programmierungen, wie sie die Natur gemacht hat, zu verlassen.

escape from the program [of culture and history]

Weibel: Von der gesamten historischen Kunstproduktion der Welt sind nur drei Prozent übrig geblieben

Saup: Übrig im Sinne …

Weibel: Physisch, als Material. Die Menschen produzieren Bilder und Skulpturen, doch da sich niemand um die Objekte kümmert, verschwinden sie, werden weggeschmissen, vermodern. Nur drei Prozent bleiben übrig.

Saup: Das ist interessant.

Weibel: Das ist im Prinzip erschreckend, denn Kultur zielt darauf, Erfahrenes zu bewahren. Das ist der einzige Grund, wieso Menschen Bücher schreiben. Weil sie wollen, dass von ihren Erlebnissen und Gedanken später auch andere profitieren können. Kultur hat in Wirklichkeit nur den einen Sinn, nämlich Erfahrungen zu tradieren. Wenn man jedoch nun den Gedanken weiterführt, dass es wichtig ist, Erfahrungen auch wieder zu löschen, dann ist es vielleicht gar nicht so schlecht, dass nur drei Prozent der Kunst übrig bleiben.

Saup: (lacht)

Weibel: Es geht nicht darum, geschichtliches Denken abzuschaffen. Man braucht Geschichte und Erfahrung. Aber diese fast grausame Einsicht in das Überleben der Kunstwerke zeigt, dass man Geschichte und Erfahrung eben nicht nur anhäufen muss, sondern dass es auch möglich sein muss, geschichtliche Erfahrung zu löschen.

Im besten Teil des Neuen Testaments geht es um das Verzeihen. Im Vaterunser heißt es “und vergib uns unsere Schuld, wie auch wir vergeben unseren Schuldigern”. Vergeben heißt nichts anderes, als dass ich die Erfahrung wirklich lösche. Deshalb interessiert mich dieses christliche Programm. Wie kann ich aus der Erfahrung, aus der Geschichte herauskommen? Indem ich einfach sage, ich lösche das, was du mir angetan hast.

forgiving the program

Weibel: Es ist irgendwie ein bisschen unangenehm, dies zu sagen. Aber wenn man über viele Jahre selbst Kunst macht, wird man immer weniger empfänglich für die Kunst anderer. Kannst du, wenn du Musik hörst, einfach dazu wippen und tanzen oder analysierst du unwillkürlich, ob diese oder jene Sequenz gut gemacht ist? Wie empfindest du die Musik? Kannst du gleichzeitig konsumieren wie analysieren?

Saup: Ich genieße es, wenn jemand musikalisch etwas aufbaut und mich dann völlig mit einer absoluten Kehrtwendung überrascht. Ich versuche so wenig Information wie möglich unbewusst in mich eindringen zu lassen. Ich lasse mich ungern manipulieren von Sachen, die ich nicht für gut befinde.

Weibel: Die offizielle Musik, im Fernsehen und im Radio, kann ich nicht mehr hören, denn sie ist so vorhersagbar. Es gibt kaum mehr Musik, die mich überraschen kann. Deshalb will ich meine Zeit nicht mehr dafür verwenden, mich hinzusetzen und eine Stunde nur Musik zu hören.

Saup: Ich glaube, dass jetzt ein Moment des Verzeihens wieder angebracht wäre. Wenn ich zum Beispiel in einen Club gehe, versuche ich immer dem Programm, dem allgemeinen Programm, auf die Schliche zu kommen: dem Programm der Fortpflanzung und dem Spiel drumherum. Musik ist eine Ausprägung dieses Programms, eigentlich eine sehr schöne. Ich habe mich dazu entschlossen, dem ganzen durchschaubaren Programm, das auch Musik in sich trägt, zu verzeihen. Letztendlich.

Weibel: Ich finde es sehr interessant, dass du eigentlich immer der analytische Beobachter bist. Du sprichst von der Durchschaubarkeit des evolutionären Programms, sozusagen der DNA. Du bist eigentlich immer interessiert, das Programm zu durchschauen.

Saup: Ja.

Weibel: Und dieses Programm kann sowohl ein genetischer Code als auch ein Musikcode sein. Im Grunde betrachtest du alles als Programmcode, sei es Musik, seien es Bilder, seien es Menschen, sei es Verhalten, du versuchst, den Code zu durchschauen. Du verzeihst jedoch der Durchschaubarkeit. Dadurch kannst du dich mit dem Programm überhaupt erst versöhnen. Sonst hättest du eine Feindschaft den Menschen gegenüber, der Welt, den Gegenständen, den Tieren. Diese Feindschaft würde dich selber auslöschen. Du verzeihst der Natur die Durchschaubarkeit ihres Programms, das eigentlich nicht gut ist.

Saup: Das ist schön … (lacht)

Weibel: Und dadurch, dass ich dem Programm verzeihe, kann ich eigentlich wieder weiterleben und weiter arbeiten. In welcher Weise haben dir die Medien Möglichkeiten angeboten, diese Durchschaubarkeit voranzutreiben und gleichzeitig zu verzeihen? Hast du bei den Medien Hilfe gefunden?

Saup: Beim Verzeihen hab ich bei den Medien keine Hilfe gefunden …

Weibel: Eher beim Bekämpfen?

Saup: Ich konnte mich selber programmieren, ich konnte ja praktisch die Bilder selber in beliebiger Reihenfolge oder die Töne oder die Lichter auf mich einwirken lassen. Dadurch habe ich erkannt, wie andere versuchen, mich zu programmieren, oder mir, freundlicher gesagt, Verhaltensmuster nahelegen. Ich sehe Rhythmen und Muster, die mich verlangsamen oder schneller denken lassen und so weiter, das, was auch chemische Substanzen tun können.

Weibel: Die Medien haben dir eigentlich geholfen, die Feindschaft, den Abgrund zwischen dir und der Welt zu meistern, indem sie dir gezeigt haben, wie du über die Sinnesorgane von der Welt programmiert wirst.

Saup: Richtig.

Weibel: im Hollywood-Kino mit seiner Überwältigungsästhetik wirst du ständig wie eine Laborratte mit Signalen überfordert und sollst entsprechend reagieren. Das geht mir auf die Nerven. Das ist keine Kunst. Über deine Schnittstelle, Körper, Gehirn, Gedanken spürst du, wie die anderen versuchen, dich zu programmieren.

Du hast mithilfe der Medien gelernt, die Durchschaubarkeit der Programme dieser Welt zu erhöhen. Du hast gesehen, dass du selbst programmieren, selbst navigieren kannst. Das hat dir geholfen, dich zu befreien von der Gewalt der Welt, die dich immer programmieren wollte.

Die Medien zeigen, dass die Welt eine steuerbare Angelegenheit ist. Und damit nimmt man der Welt auch die Wucht. Du durchschaust das Programm und machst ein Gegenprogramm. Du zeigst, dass das Gewicht der Welt nur eine Fiktion ist, mit der sie versucht, dich zu erdrücken. Dies ist möglich, wenn man die Medien nicht für die Abbildung der Welt benutzt, und wenn man nicht, wie Bill Viola, Hollywood-Ästhetik erzeugt, die auch leider nur mit Spezialeffekten überwältigen will. Ich fühle mich in seinen Installationen genauso unwohl wie in Filmen von Steven Spielberg.

Saup: Ich gebe dir völlig recht.

Weibel: Dabei sollten die Medien in Wirklichkeit zeigen, wie das Programm der Welt oder der Natur funktioniert. Sie sollten es durchschaubar machen. Denn dies gibt einem die Möglichkeit, das Programm umzugestalten.

Saup: Das ist richtig.

Weibel: Ich glaube, darum geht es bei deiner eigenen Kunst. Du hast Musik und Bilder gebraucht, um die Durchschaubarkeit des Programms nicht nur zu erkennen, sondern selbst das Programm ändern zu können. Als Gegengewicht sozusagen. Du verzeihst dem Programm seine Durchschaubarkeit, doch die Medien sind Instrumente der Kriegsführung.

Saup: Das Verzeihen war eine Lektion, die außerhalb der Medien liegt.

transcending the program [of death]

Weibel: Der Tod ist der Motor der Evolution. Sie kann nur funktionieren, wenn Individuen und ganze Arten aussterben. Ohne den Tod würde auch auf historischer Ebene eine unglaubliche Dynamik verloren gehen. Dann hätten wir immer noch den 134-jährigen Zaren von Russland. Doch wenn Menschen verschwinden, können neue Systeme und Ideen entstehen.

Ich kämpfe jedoch nicht für den Tod, sondern versuche, ihn einzuschränken: wir Menschen nehmen an dieser Evolution so kurz teil, dass wir sie nicht einmal beobachten können. Da wird ein riesiges Theaterstück gespielt auf der Bühne und wir sehen davon nichts. Darum möchte ich gerne, dass wir dieses winzige Fenster, diese achtzig Jahre, ein bisschen ausdehnen können. Damit ich ein bisschen mehr verstehe von diesem Theaterstück.

Durch die Medien kann ich den Horizont erweitern, die Grenzen überschreiten, die mir die Evolution gesetzt hat. Wenn die Medien eigentlich schon mit Träumen beginnen, dann haben sie genau diese Aufgabe: nämlich zu versuchen, dieses winzige Fenster zu dehnen, damit ich ein bisschen mehr sehe von der Evolution. Ich kann beispielsweise simulieren, wie Dinosaurier ausgesehen haben oder ein Bild der Welt in 100 Jahren entwerfen.

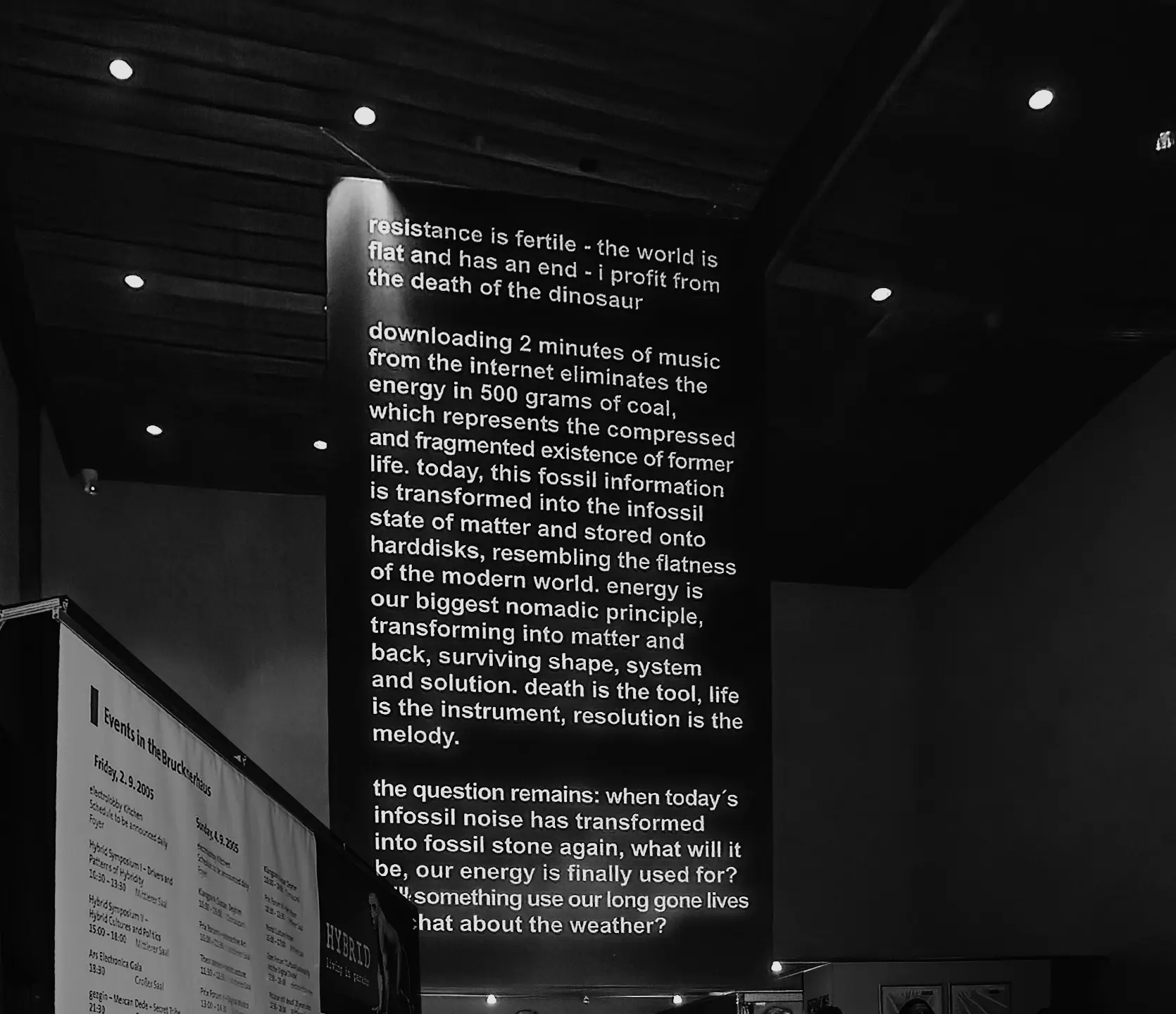

Saup: Es geht um das Fossile und das Infossile. Eine E-Mail oder zwei Minuten Musik, die aus dem Netz gezogen werden, kosten etwa 500 Gramm Kohle. Die Kohle ist das alte Gedächtnis der Welt. Wie hätten sich die Saurier je denken können, wofür sie eines Tages Energie spenden würden? Dieser gedankliche Schritt ist unvorstellbar. Es wäre interessant zu fragen, wofür unser heutiges infossiles Rauschen, wenn es fossilisiert ist, Energie spenden wird.

Weibel: Deine Kunst ist tief verankert in diesem Wunsch, Raum und Zeit zu überwinden. Das Fossile sind die Reste der Evolution, die den Tod überschreiten. Die Jahrtausende alte Kohle ist die Energiequelle für heutige Kultur. Es gelingt hier sozusagen, über unseren Zeitradius hinauszuspringen und auf Erfahrungen und Informationen zurückgreifen, die uns heute ernähren. Die Möglichkeit, aus dem Fossilen Energie zu gewinnen, hat eine ungeheure kulturelle Leistung erbracht. Etwas, was eigentlich tot ist, und von der Evolution verabschiedet ist, kann noch mal für das Leben benutzt werden. Das sind eigentlich schon die ersten medialen Vorgänge. Es ist sehr interessant, dass du die Medienpraxis in Bezug setzt zum Fossilen. Die fossilen Brennstoffe zeigen, dass die Medien die Tendenz haben, die Gesetze der Evolution, deren Kern der Tod ist, zu überspringen.

Saup: So war es und so sei es.

INFOSSIL – AD VITAM

A Conversation between Peter Weibel and Michael Saup, Karlsruhe, 2002

Saup: Where I grew up, I couldn’t talk to anyone. I therefore went into the virtual, into the future or the past. Navigating in the void was the central basis of survival.

Weibel: I also created my own worlds as a child. Perhaps the prerequisite for becoming an artist is that you automatically start looking for other worlds. There was no one I wanted to talk to. On the contrary, I tried to withdraw from the whole social community. The normal outside world was rather disturbing for me. You also secluded yourself early on?

Saup: yes.

Weibel: … and talk to yourself all the way back over centuries.

Saup: The first medium I consciously used was dreams. After that it was music, then my father’s camera, which was in a closet. I stole it at night and then exposed short scenes in my room. Around 1980, I started working with computers. I saw that I could hack, but that I didn’t have to know how to program at all to do it. I can just interfere with the coding that’s there. I can destroy it and something new happens. That fascinated me. All that was a help to escape from now or to build a road to the future.

Weibel: That you started with dreaming fits in with my theory that media and technology spring from a morphology of desire. Wishes, desires, longings seek some form of expression, a shape in which they articulate themselves. So maybe the media only continue the work of dreams. One communicates with things that are neither spatially nor temporally there. Through media, I can bridge the distance, the dislocation. Dreams do just that: they make the absent present. One dreams and thereby creates new experiences for oneself.

escape from the program [of experience]

Weibel: But experience also forms a prison. For example, if I offer bread to a person five times and he beats me for it each time, then I simply know that giving bread means being beaten. You can’t get rid of that experience. A cat that has jumped on a hot stove top will not do it again.

It would actually be better if you could erase that experience, even at the risk of getting burned again. But then one can always encounter the world anew: with this impartiality, with this optimism. In this way, however, people become skeptical and distrustful. They are locked into their experience. I keep trying to erase that experience. The price is very high, but I don’t want to be locked into that experience, into that prison.

Saup: interesting idea …

Weibel: You create a story for yourself. Then you become prisoner of this story, experience aims to avoid pain and harm. At the same time, this limits my ability to have new experiences. My horizon becomes narrower and narrower, and the older you get, the worse this becomes.

Thank God, young people have little experience. Due to lack of experience, they plunge into adventures that those more experienced advise them against. But since they are not prisoners of history, they do it and it goes well.

Saup: The prison of experience is particularly tragic because local experience is naturally applied to the global. Experience keeps you from knowing anything at all that is outside your local culture.

Weibel: You become a prisoner, a prisoner of the particular. In another place, in other cultural circles, the individual might act quite differently. But the experience of multiplicity is blocked. I do not believe in the experience of the universal. There are few constants. There is only the multiplicity of differences. But this multiplicity is not made accessible to one, because one binds oneself too much to the local particular experience, which one has made here and now.

Art should make it possible to erase experiences by allowing new experiences to be made. But this rarely succeeds.

escape from the program [of nature]

Weibel: There is knowledge that evolution has imprinted. The ground squirrel knows how to react to a rattlesnake without ever having seen a rattlesnake. It’s that chip. The animal’s reaction is not learned; rather, the historical experience is genetically imprinted. This is the only way nature can allow its creatures to survive. The animals are prisoners of the historical experience.

Saup: The program is …

Weibel: We are prisoners of the program, but we want to be more. If we want to be human beings, we have to pay the price of deleting experiences again. Then we have to delete the program. But only very few people do that, because it involves risks and because it can lead to harm. It would actually pay off. In order to develop as a human being, it would be necessary to leave precisely this programming, as nature has made it.

escape from the program [of culture and history].

Weibel: Of all the historical art production in the world, only three percent remains.

Saup: Remaining in the sense …

Weibel: Physically, as material. People produce pictures and sculptures, but since no one takes care of the objects, they disappear, are thrown away, rot. Only three percent remain.

Saup: That’s interesting.

Weibel: In principle, that’s frightening, because culture aims to preserve what has been experienced. That’s the only reason why people write books. Because they want others to benefit from their experiences and thoughts later on. Culture has in reality only the one sense, namely to hand down experiences. However, if you now take the idea further that it is important to also erase experiences, then perhaps it is not such a bad thing that only three percent of art remains.

Saup: (laughs) …

Weibel: It’s not about doing away with historical thinking. You need history and experience. But this almost cruel insight into the survival of works of art shows that one must not only accumulate history and experience, but that it must also be possible to erase historical experience.

The best part of the New Testament is about forgiveness. The Lord’s Prayer says ‘and forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us’. Forgiveness means nothing more than really erasing the experience. That’s why I’m interested in this Christian program. How can I get out of the experience, out of the history? By simply saying, I erase what you did to me.

forgiving the program

Weibel: It’s somehow a bit unpleasant to say this. But when you make art yourself for many years, you become less and less receptive to the art of others. When you hear music, can you just bob and dance to it, or do you involuntarily analyze whether this or that sequence is well done? How do you feel about the music? Can you consume as well as analyze at the same time?

Saup: I enjoy it when someone builds something up musically and then completely surprises me with an absolute about-face. I try to let as little information as possible enter me unconsciously. I don’t like to be manipulated by things that I don’t think are good.

Weibel: I can no longer listen to the official music, on television and on the radio, because it is so predictable. There is hardly any music left that can surprise me. That’s why I no longer want to spend my time sitting down and listening to nothing but music for an hour.

Saup: I think that now a moment of forgiveness would be appropriate again. When I go to a club, for example, I always try to get to the bottom of the program, the general program: the program of reproduction and the game around it. Music is a manifestation of this program, actually a very beautiful one. I have decided to forgive the whole transparent program, which also has music in it. Ultimately.

Weibel: I find it very interesting that you are actually always the analytical observer. You talk about the transparency of the evolutionary program, the DNA, so to speak. You’re actually always interested in seeing through the program.

Saup: Yes.

Weibel: And this program can be both a genetic code and a musical code. Basically you look at everything as program code, be it music, be it pictures, be it people, be it behavior, you try to see through the code. However, you forgive the see-through. That’s what allows you to reconcile with the program in the first place. Otherwise you would have an enmity towards people, the world, objects, animals. This enmity would extinguish you. You forgive nature for the transparency of its flawed program.

Saup: That’s beautiful … (laughs)

Weibel: And by forgiving the program, I can actually go on living and working again. In what ways did the media offer you ways to push this transparency and forgive at the same time? Did you find help from the media?

Saup: I haven’t found any help from the media in forgiving …

Weibel: Rather in fighting?

Saup: I could program myself, I could practically let the images themselves affect me in any order or the sounds or the lights. Through this, I recognized how others try to program me, or, to put it more kindly, suggest patterns of behavior to me. I see rhythms and patterns that make me slow down or think faster and so on, that which chemical substances can also do.

Weibel: The media actually helped you master the enmity, the chasm between you and the world, by showing you how you are programmed by the world through the sense organs.

Saup: Right.

Weibel: in Hollywood cinema, with its overwhelming aesthetics, you are constantly overwhelmed with signals like a lab rat and are supposed to react accordingly. That gets on my nerves. That’s not art. Through your interface, body, brain, thoughts, you feel others trying to program you.

You have learned with the help of the media to increase the transparency of the programs of this world. You have seen that you can program yourself, navigate yourself. This has helped you to free yourself from the violence of the world that always wanted to program you.

The media shows that the world is a controllable thing. And in doing so, you also take the force out of the world. You see through the program and make a counter-program. You show that the weight of the world is only a fiction with which it tries to crush me. This is possible if you don’t use the media to depict the world, and if you don’t, like Bill Viola, create Hollywood aesthetics that also, unfortunately, only want to overwhelm with special effects. I feel as uncomfortable in his installations as I do in Steven Spielberg’s films.

Saup: I agree with you completely.

Weibel: In reality, the media should show how the program of the world or of nature works. They should make it transparent. Because that gives you the opportunity to reshape the program.

Saup: That’s right.

Weibel: I think that’s what your own art is about. You needed music and images not only to recognize the transparency of the program, but also to be able to change the program yourself. As a counterweight, so to speak. You forgive the program its transparency, but the media are instruments of warfare.

Saup: Forgiveness was a lesson that lies outside the media.

transcending the program [of death].

Weibel: Death is the engine of evolution. It can only function if individuals and entire species die out. Without death, an incredible dynamic would also be lost on a historical level. We would still have the 134-year-old Tsar of Russia. But when people disappear, new systems and ideas can emerge.

However, I do not fight for death, but try to limit it: we humans participate in this evolution so briefly that we cannot even observe it. There is a huge play being played on stage and we see nothing of it. That’s why I would like us to be able to extend this tiny window, these eighty years, a little bit. So that I can understand a little more of this play.

Through the media I can expand the horizon, go beyond the limits that evolution has set for me. If the media actually already start dreaming, then they have exactly this task: namely, to try to stretch this tiny window so that I can see a bit more of evolution. For example, I can simulate what dinosaurs looked like or create a picture of the world 100 years from now.

Saup: It’s about the fossil and the infossil. An e-mail or two minutes of music pulled from the net costs about 500 grams of coal. Coal is the ancient memory of the world. How could the dinosaurs ever have imagined what they would one day donate energy to? This mental step is unimaginable. It would be interesting to ask what our present infossil noise, when fossilized, will donate energy to.

Weibel: Your art is deeply anchored in this desire to overcome space and time. The fossil is the remains of evolution that transcend death. Coal, which is thousands of years old, is the source of energy for today’s culture. It succeeds here, so to speak, to jump beyond our time radius and to fall back on experiences and information that nourish us today. The ability to extract energy from the fossil has been a tremendous cultural achievement. Something that is actually dead, and passed by evolution, can be used again for life. These are actually already the first medial processes. It’s very interesting that you relate media practices to the fossil. The fossil fuels show that the media have the tendency to skip the laws of evolution, the core of which is death.

Saup: So it was and so be it.

Peter Weibel was born in Odessa in 1944 and studied literature, medicine, logic, philosophy, and film in Paris and Vienna. He became a central figure in European media art on account of his various activities as artist, media theorist, curator, and as a nomad between art and science.

From 1984 until 2017, he has been a professor at the University of Applied Arts Vienna. From 1984 to 1989, he was head of the digital arts laboratory at the Media Department of New York University in Buffalo, and in 1989 he founded the Institute of New Media at the Städelschule in Frankfurt on the Main, which he directed until 1995. Between 1986 and 1995, he was in charge of the Ars Electronica in Linz as artistic director. From 1993 to 2011 he was chief curator of the Neue Galerie Graz and from 1993 to 1999 he commissioned the Austrian pavilion at the Venice Biennale. He was artistic director of the Seville Biennial (BIACS3) in 2008 and of the 4th Moscow Biennial of Contemporary Art, in 2011. From 2015–2017, he was curator of the lichtsicht 5 + 6 – Projection Biennale in Bad Rothenfelde.

Peter Weibel was granted honorary doctorates by the University of Art and Design Helsinki, in 2007 and by the University of Pécs, Hungary, in 2013. In 2008, he was awarded with the French distinction »Officier dans l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres«. The following year he was appointed as full member of the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts Munich, and he was awarded the Europäischer Kultur-Projektpreis [European Cultural Project Award] of the European Foundation for Culture. In 2010, he was decorated with the Austrian Cross of Honor for Science and Art, First Class. In 2013 he was appointed an Active Member of the European Academy of Science and Arts in Salzburg. In 2014, he received the Oskar-Kokoschka-Preis [Oskar-Kokoschka-Prize] and in 2017 the Österreichische Kunstpreis – Medienkunst [Austrian Art Prize – Media Art], and in 2020 the Lovis-Corinth-Preis. In 2015 he was appointed as Honorary Member of the Russian Academy of Arts in Moscow.

From 1999 until 2023, Peter Weibel was Chairman and CEO of the ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe and since 2017 director of the Peter Weibel Research Institute for digital Cultures at the University of Applied Arts Vienna.

On March 1, 2023, he passed away in Karlsruhe after a short serious illness at the age of 78.

Michael Saup is an artist, instrumentalist, coder, teacher and filmmaker. He has acted as professor of digital media art at HfG/ZKM Karlsruhe University in Germany and as the founding director of the Oasis Archive of the European Union. He is the co-founder of the Open Home Project, a humanitarian initiative to help people being affected by nuclear disaster. Amongst others, his work has been awarded by the Ars Electronica and the UNESCO Commission. Michael Saup’s work focuses on the underlying forces of nature and society; an ongoing research into what he calls INFOSSIL – the “Archaeology of Future”. His work has been shown widely in exhibitions, festivals and on stages around the world. He currently lives and works in Berlin.